Make it a Habitat

The Six Secrets of Gardening for Wildlife

It seems every other documentary these days has the word “Secrets” in its title, as in “Secrets of the Pyramids,” or “Secrets of the National Parks,” or “Secrets of…” Well, you get the idea. What these documentaries also happen to have in common is a distinct lack of any actual secrets.

And so, it is with a sense of being in total alignment with the zeitgeist that I unveil this list of six, not-so-secret “secrets” of habitat gardening. Drawn from over a decade of experience tending the LA Native Plant Source garden, I hope that these tips, while somewhat self-evident, will prove useful to those native plant gardeners who’d like to attract (and support) more bugs, birds, lizards and other wild creatures to their own little slice of California.

Secret Number 1: Plant the plants that grow wild where you garden

While imported exotic insects like the generalist European Honey Bee may be perfectly happy foraging on pretty much whatever happens to be growing nearby, many native species depend upon a more specific set of plants for their sustenance and survival. A successful habitat gardener will therefore supply local wildlife with the plants they instinctively recognize as food.

If you’ve been gardening with California’s native plants for any length of time, your reaction to this first, so-called “secret” is likely to be “Oh, really? Gee thanks, Captain Obvious.” To be fair, however, it’s important to clarify that not every plant that’s native to California will necessarily look like dinner to the animals in your neighborhood. The California Floristic Province stretches from Baja to Southern Oregon, after all. While virtually every non-exotic plant growing wild within that gargantuan range may be considered a “California native,” that doesn’t mean sticking a Mendocino County species like Coast Redwood in a Los Angeles County garden will either attract or support the animals who live here. (Not to mention that the unfortunate seedling will most likely live out its pathetic and stunted life wondering, “Where’s my fucking coastal fog?”)

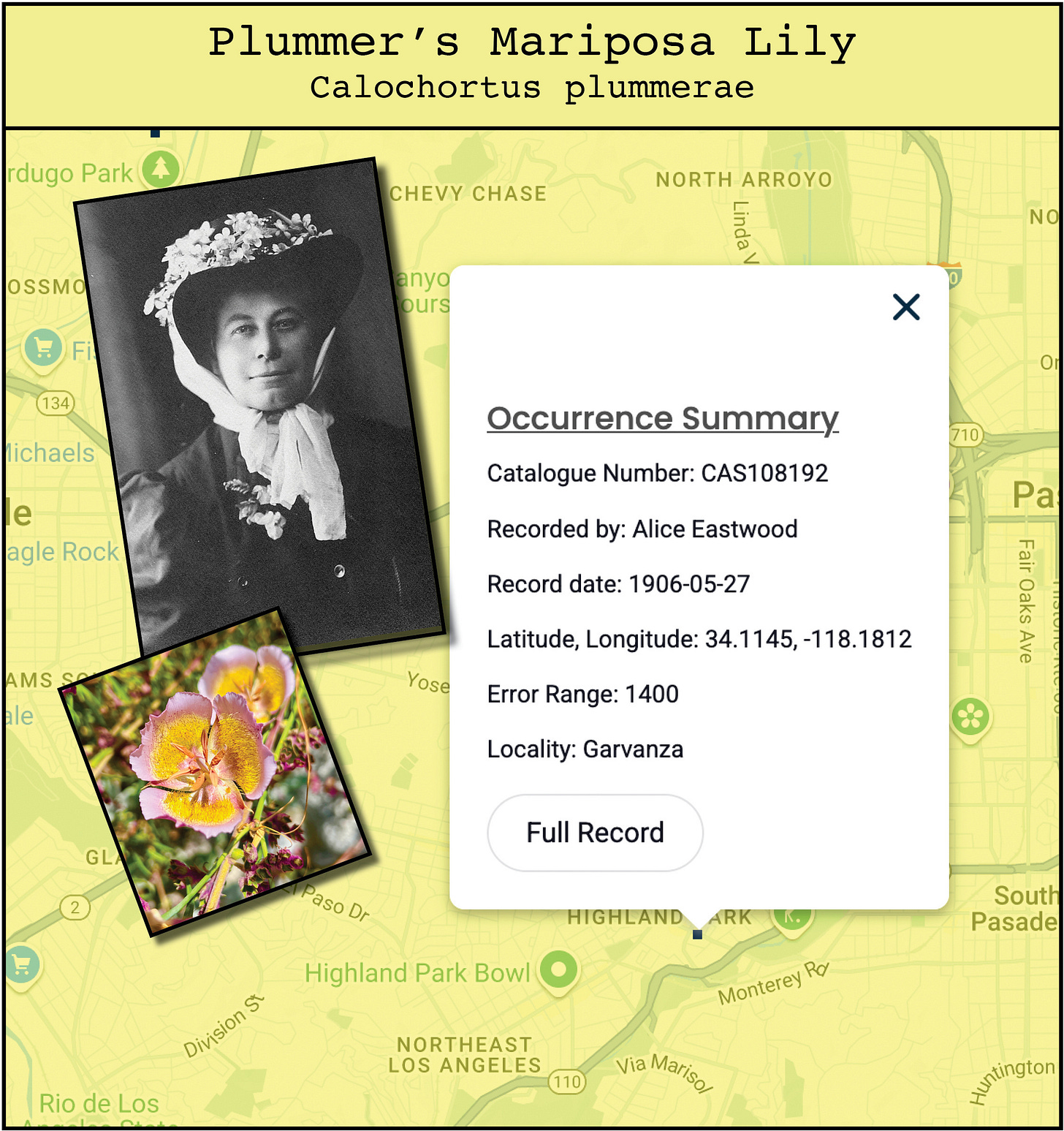

Once you’ve committed to going “hyper-local” (or hyper-local-ish) it can admittedly be a bit of a challenge to figure out which plant species are truly native to your garden and will thus provide the most sustenance to the animals who live there. This is especially true if you happen to be in an area where all, or nearly all native plants were extirpated long ago. Luckily, if you’re not sure what grows (or grew) wild in your area, there’s an easy way to find out: go to calscape.org and click on “Find Native Plants.” Simply enter your zip code, and voila: you’ll get a long, rather overwhelming list of plants whose estimated natural range matches your location. (And when I say “long,” I mean long: according to Calscape’s search widget, the LA Native Plant Source garden’s zip code is home to over 700 plant species!)

From there, you can do a deeper dive if you’d like, exploring specific botanical sightings in your immediate vicinity by clicking on the little blue squares that populate the “Estimated Plant Range” map for each species. You may discover that many native plants could once be found growing in your environs, but that it’s been a long time since they were last observed. Restoring these vanished plants to the landscape is one of the most effective ways you can support the wildlife in your community, and with Calscape, it’s never been easier.

PRO TIP: When it comes to habitat value, if you have a choice between the straight species and a cultivar of a given plant at the nursery, always choose the species. Not only does it promote biodiversity, but no less impeccable a source than The Xerces Society notes that some native cultivars may be less attractive to pollinators.

Secret Number 2 – Plant More Than One

Before you run out and plant as many species from your Calscape list as you can cram into your necessarily limited amount of gardening space, consider this: the micro-environment within a given wild landscape typically features a relatively narrow, repeating subset of plants that are well suited to its particular conditions. The fact that plants are stationary lifeforms means their proliferation strategies, while ingenious, are necessarily limited. Outside the phenomenon of endozoochory1, plants tend to spread gradually outward into their immediate area. This happens to intersect nicely with the fact that broad visual fields of the same flower are easier for pollinators to recognize than isolated specimens.

In other words, a “one-of-each” botanical garden of native plants, while it may stimulate the pleasure centers of your variety-loving human brain, will likely prove much less appealing to your local pollinators. Admittedly, limiting the number of plant species in your garden to make room for multiples takes a little discipline – especially if you have limited space – but if your objective is to attract and support wildlife, you might consider foregoing novelty in favor of repetition at least some of the time.

PRO TIP: Treat your pollinators to masses of clustered, yellow flowers by broadcasting the seeds of the low-growing, long-blooming herbaceous perennial Golden Yarrow (Eriophyllum confertiflorum) in the sunny spaces between your maturing Chaparral shrubs. This local species, which, in my experience, can be quite tricky to establish when planted from a one-gallon pot, seems to do much better when grown from seed, in situ. Broadcast in the fall once temperatures have dropped and the days have shortened. Any seedlings that make it through their first summer will bloom the following spring. (Golden Yarrow seeds are usually available through the Theodore Payne Foundation.)

Secret Number 3: Keep Things Messy

Tidiness may be a virtue indoors, but when it comes to habitat gardening, the messier the better. Taking your cue from the natural world, with its thick carpets of dead leaves, tangles of fallen branches, snags and impenetrable thickets, resist the temptation to impose more order on your garden than is absolutely necessary for access and safety.

There are multiple habitat-related benefits to letting garden detritus build up over time. First, it will furnish all kinds of ready-made hideouts and building materials for nests. At the same time, it will reintroduce the vital cycle of growth and decay to your garden’s ecosystem, providing food for bacteria, fungi, earthworms and insect larvae, which serve, in turn, as food for larger animals. In addition, an ever-thickening layer of leaves and twigs will act as a natural mulch, discouraging exotic weeds, keeping the soil cooler in summer and supplying it with an endless source of nutrients. What’s not to like?

PRO TIP: The appropriately named Western Fence Lizard seems to have an affinity for stacks of wood. If you pile up a few branches you’ve pruned, or even some scrap lumber here and there, you may just get a reptile-in-residence.

Secret Number 4: Let your plants go to seed

When taken literally, letting something “go to seed” describes one of the most important of habitat gardening practices: allowing your annuals and grasses the time they need to go through their entire reproductive cycle – from flowering to fruiting to the ripening and dropping of seed – before pruning or trimming them back for reasons of fire safety or aesthetics.

Similarly, the flowering stalks of perennials, such as sages and buckwheats, should be left to completely ripen and dehisce2 before deadheading, whenever possible. This practice is virtually guaranteed to attract ground-foraging birds like California Towhees and Mourning Doves to your resulting “all-you-can-eat” garden floor.

Finches, on the other hand, prefer devouring seeds before they drop, so be sure to leave at least some seed heads to mature on the stalks of Lamiaceae and Asteraceae species like sages and sunflowers.

Pro Tip: If and when you do cut spent spring ephemerals and grasses to the ground in summer, leave some of the trimmings on the ground here and there to provide a ready source of nest-building materials.

Secret Number 5: Plant so that there is always something flowering in your garden

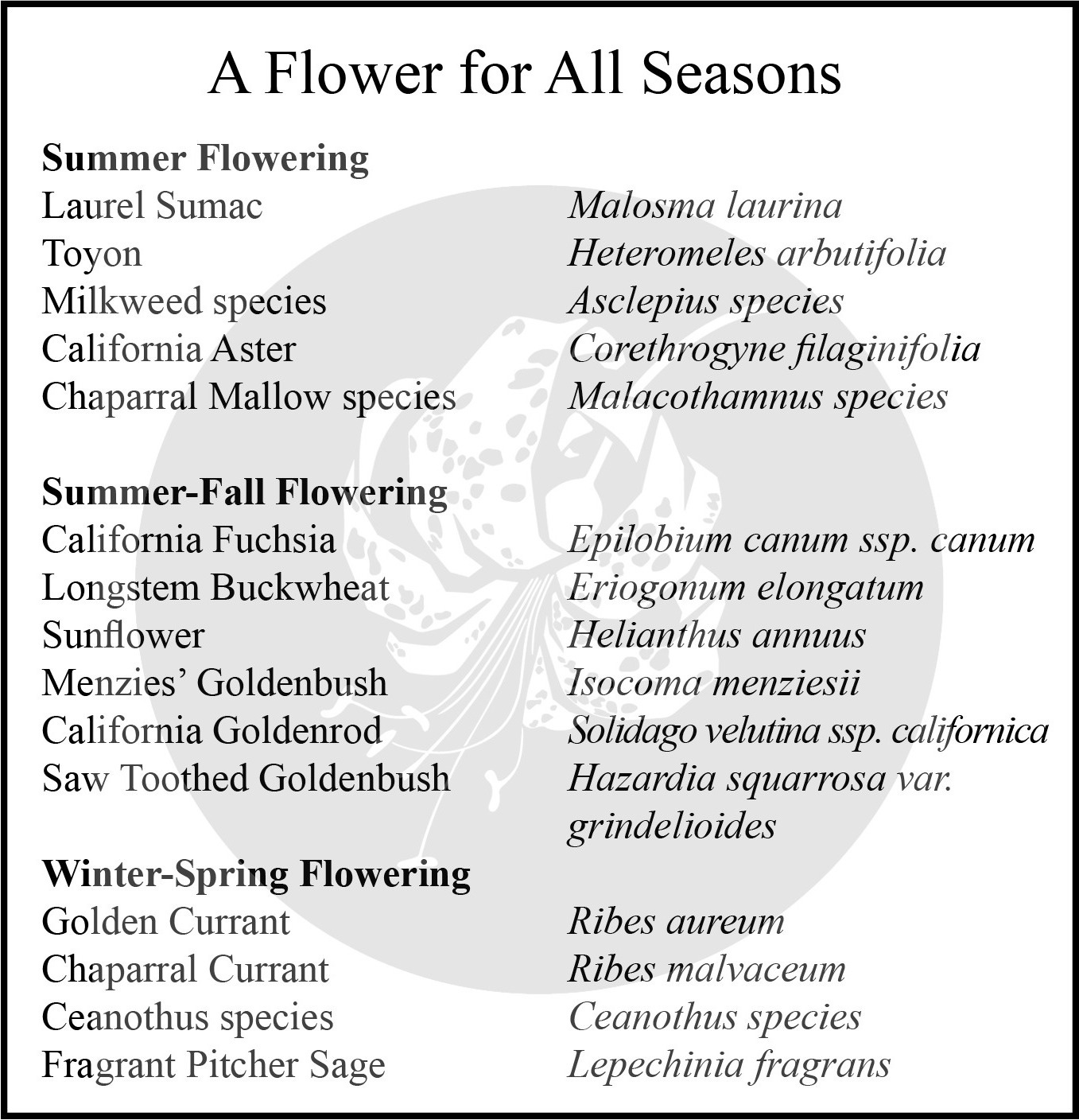

For pollinators in particular, the abundant flowering of spring is a gigantic feast. But what about the rest of the year? Making sure your habitat garden also includes plants that flower in the summer, fall and winter will attract and support successive waves of pollinators once April’s extravagant display has wound down.

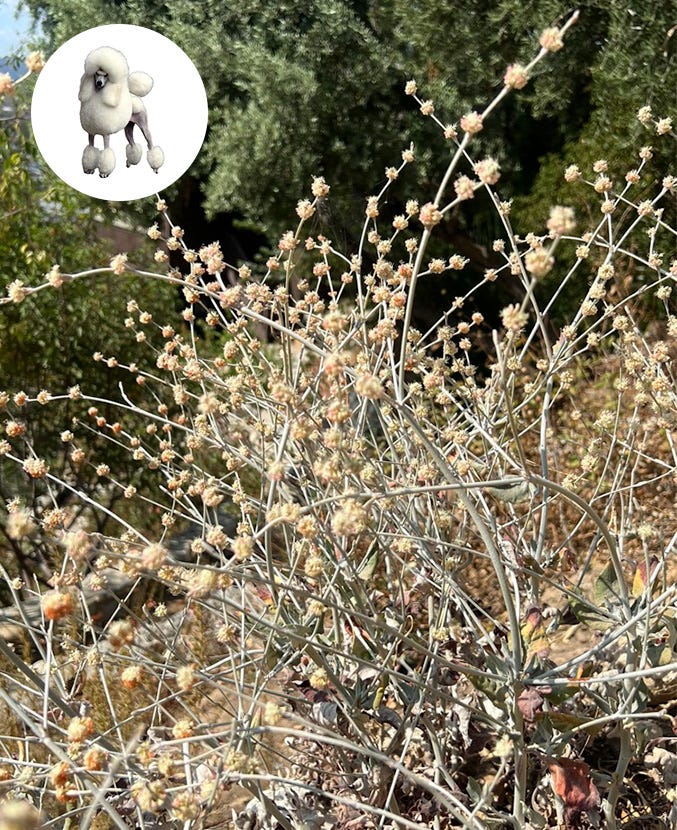

Pro Tip: One of the best and most under-utilized LA-local species for summer/fall flowers is Longstem Buckwheat (Eriogonum elongatum), which blossoms far later in the year than any other native buckwheat, providing ample amounts of nectar for pollinators at a time when there is little else in bloom.

Secret Number 6: It’s the Water, Stupid

One of the most harmful consequences of the wholesale development of wild land in the Los Angeles area over the past two centuries has been the destruction of the region’s freely flowing waterways, many of which are now buried under miles of asphalt and cement. In such a heavily degraded environment, it is imperative that we supply local animals with alternative sources of water. One way to do this is by turning each of our gardens into an oasis with a “water feature.” Doing so is also, quite possibly, the single-most effective way to draw animals to your garden and keep them coming back for more.

Birds in particular will literally flock to birdbaths, ponds and fountains, especially in warm weather, and they have the ability to recall the precise location of water sources over long periods of time for return visits. Adding movement to the water with a simple, immersible pump, solar fountain or “Water Wiggler” gizmo will increase the allure of whatever water feature you have, as birds find the sound and sparkle of splashing or rippling water to be utterly irresistible.

By adding water to food and shelter, you’ll be providing a kind of “Amazon Prime” environment for wildlife, in which everything they could possibly want or need can all be found in one place. You basically want the animals visiting your garden to think (as if they actually could), “Why on earth would I go anywhere else?”

Pro Tip: Create a watering hole for butterflies and bees by wetting a bare patch of dirt in your garden throughout the summer. If possible, choose a spot with slow drainage so that you end up with a long-lasting patch of mud.

Epilogue: Sex

To find a member of its own species with which to mate and reproduce is undoubtedly one of wildlife’s most powerful instincts. Happily, if you employ some or all of the above “Six Secrets” to your garden – thereby creating an environment that is attractive to a female of a given species – it should be just as attractive to a male of the same species. In this way, a well appointed habitat garden acts, by default, as the vegetative equivalent of a dating app.

– Eric Ameria

A ten-dollar word describing the process by which an animal grazes on a plant’s fruit, and then deposits the seeds somewhere else through its feces. This obviously gives plants a degree of mobility otherwise unavailable to them. As it passes through the animal’s digestive tract, seeds are also exposed to hydrochloric acid, rendering them more likely to germinate as their hard, outer coating is dissolved.

From the Latin word meaning “to split open.” A seed pod is said to dehisce when it bursts apart, discharging its contents.

Another highly informative and entertaining read! Merle (the burl) particularly liked the part about coastal fog. And Alice Eastwood, wow!